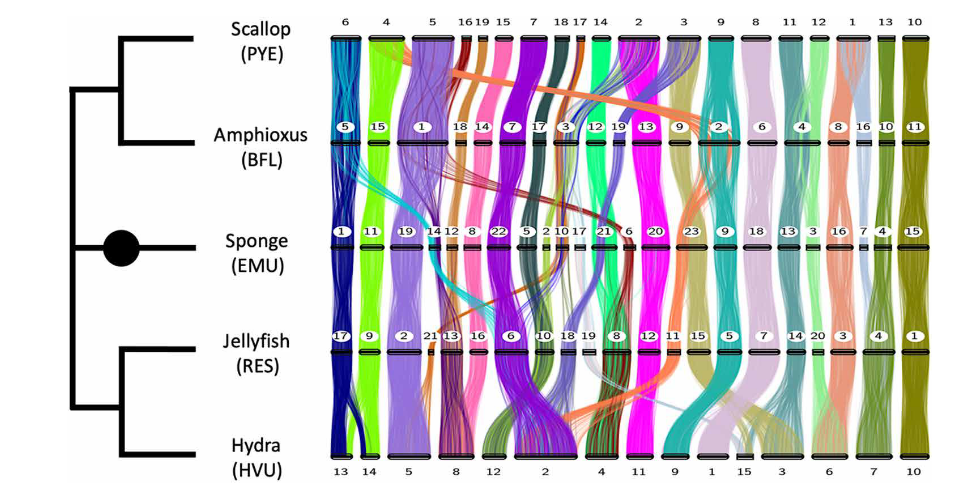

When groups of genes are together on the same chromosome they are called ‘in synteny’. Across distant animals such as Scallops, Vertebrates, and even Sponges and Jellyfish, synteny has been conserved.

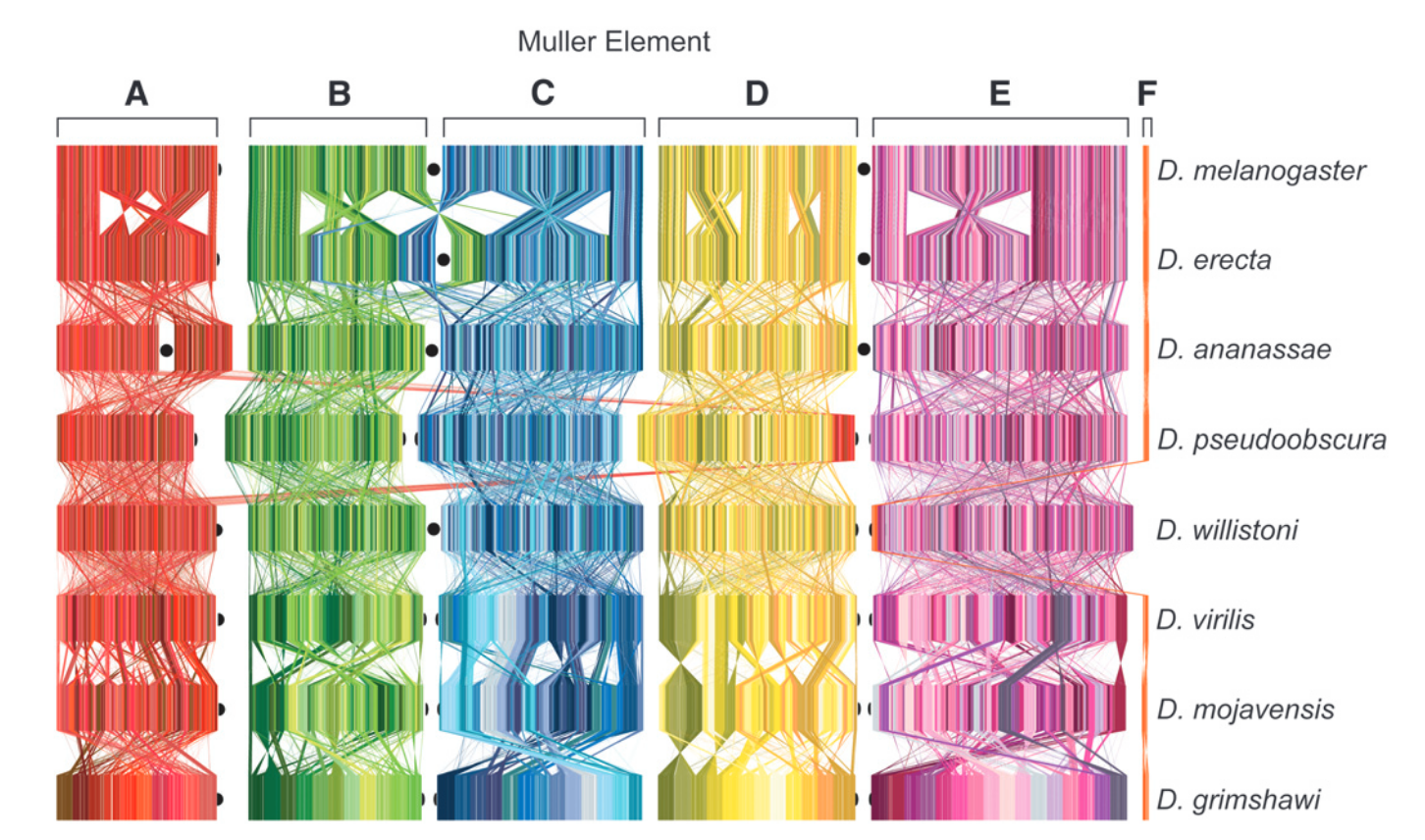

However, some groups such as round worms or insects have shuffled their genes so much that we cannot detect these linkage groups anymore. Interestingly, in both groups new syntentic groups have been established (e.g., Muller elements in Drosophila).

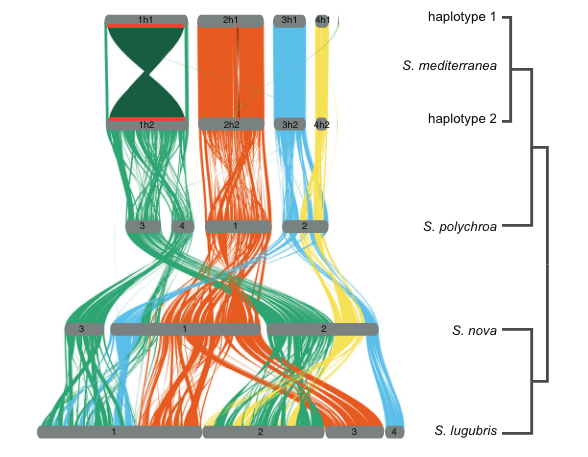

In our newest paper, we investigated synteny in our beloved flatworms and found that while synteny is partially conserved in parasitics flatworms, it is not conserved in the planarian genus Schmidtea or the early-branching Macrostomum hystrix. On top of that synteny between the flatworm groups is also not conserved! So the worms apppear to continuously shuffle their genome and evolve without constraints on synteny. In Schmidtea we found a high frequency of chromosomal rearrangements that appear to be associated with mobile transposable elements. That could provide a vital clue to why gene shuffling is common.

You can read more details on the story in our recent paper.